Australian photographer Glenn Porter's "Out of the Shadows" series captures the scars of this land, the stories of its people, and the silent weeping of the trees. Porter's lens focuses on the gorges, cliffs, and wilderness of New South Wales - places that were once home to Indigenous communities living in symbiosis with the land for tens of thousands of years, only to become sites of massacre, displacement, and cultural erasure after British colonizers invaded in the late 18th century.

"Historical records show that the Anaiwan people of the New England region fiercely resisted the colonizers who seized their land. Yet many were driven into the gorges—thrown off cliffs or gunned down. An oral account from an Anaiwan elder reads: 'My grandmother was killed at the cliffs near Armidale. They killed so many of our people—threw them off the cliffs, right at Wollomombi… They herded Black folks like kangaroos and shot them.'"Wollomombi Gorge, 2022 – Anaiwan Country

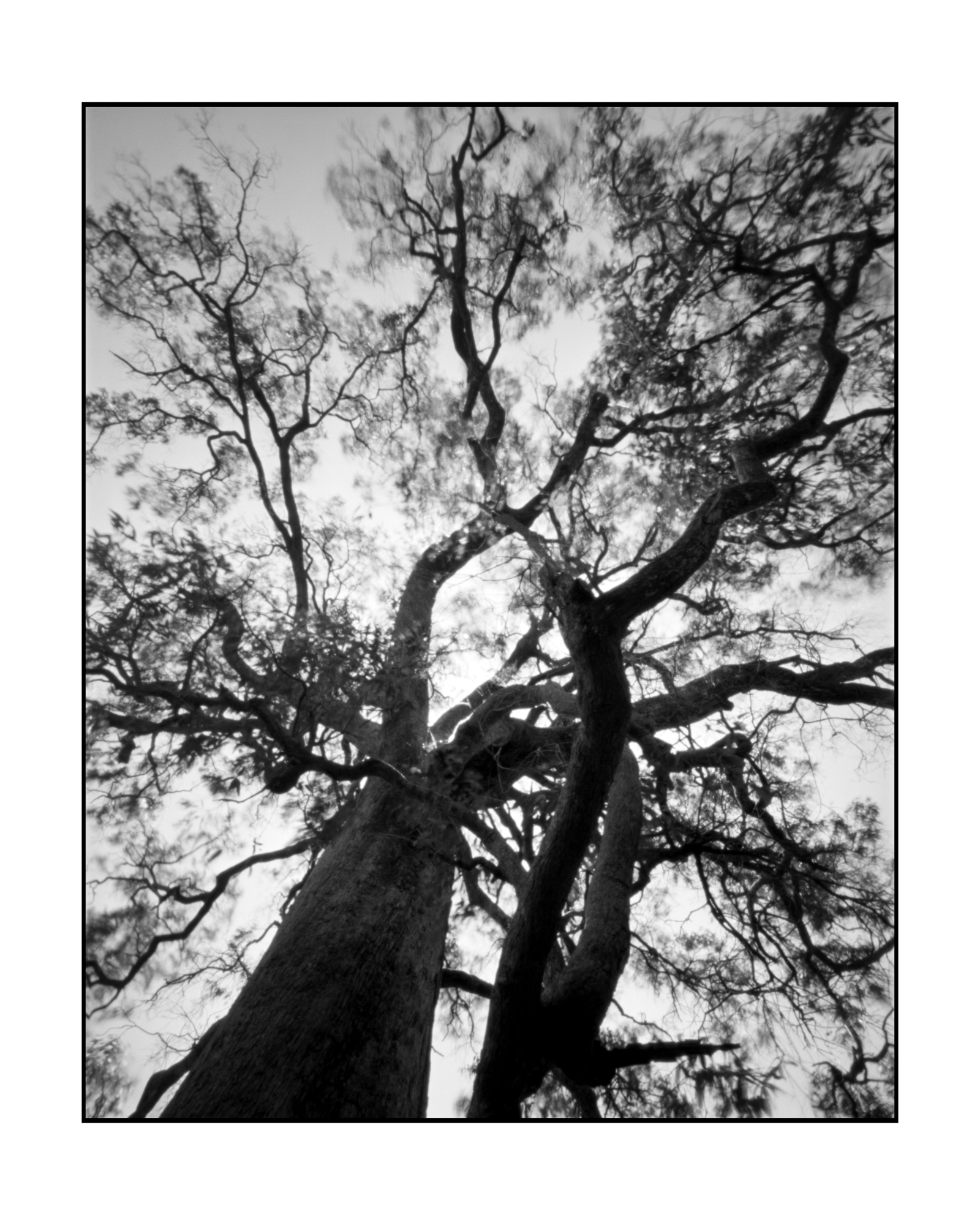

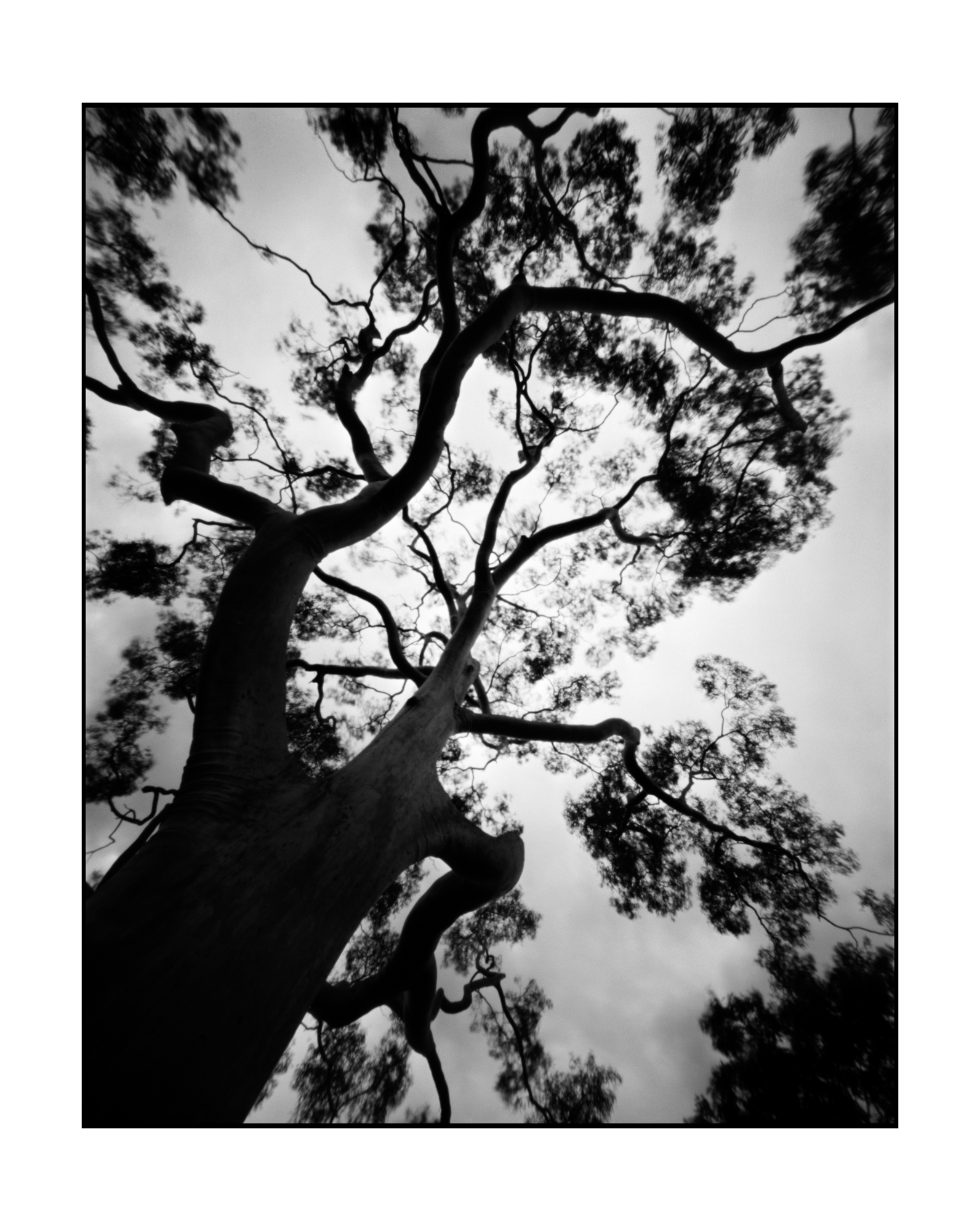

"This ancient eucalyptus stands in the valley where the atrocity occurred. In 1825, six innocent Indigenous family members were murdered here—mistaken for a group pursued by colonial forces. The tree's girth and rings suggest it may have already stood witness to the massacre. The land holds memory; landmarks like this tree and the surrounding boulders remain as reminders—evidence of history and traces of violence still rooted in this place."

Garland Valley Massacre, 2022 – Wonnarua Country

Within the context of contemporary landscape photography, these images do not merely offer an aesthetic gaze upon natural terrain. Instead, they translate "landscape" into "place"—a vessel embedded with historical violence, resistance, and cultural rupture. Here, "placeness" transcends geographical coordinates, becoming a site where colonial brutality and Indigenous spirituality intertwine—a testimonial long absent from national narratives.

The significance of "Out of the Shadows" lies in its revelation of photography's archival power and agency. While modern Australia's national identity has marginalized Indigenous suffering, Porter's lens brings sites of massacre, missionary detention, and resistance back into public consciousness. These images are not just visual evidence but an act of memory politics—by reshaping our understanding of place, photography forces society to confront historical plurality, redefining *"belonging"* within the tension of trauma and reconciliation.

Glenn Porter's work reminds us that landscapes are never neutral. In the contemporary context, places are intersections of layered memory, violence, and spirituality. His images are both an indictment of colonial history and an homage to Indigenous worldviews—the land is silent, but it never forgets. In an era where national narratives still seek to gloss over wounds, perhaps this is photography's mission: to transform places into unhealed scars, compelling viewers to hear the weeping of trees and the cry of the land.